Learning Psychology: The Ultimate Guide to Build Next-Gen EdTech Products (1/2)

Thinking EdTech Products by First Principles

When I see the discussions within the EdTech scene, there is one thing I keep noticing:

We are far too obsessed with learning technologies and formats, when we should actually be obsessed with learning outcomes.

Let me explain:

It’s great to see how EdTech keeps adopting new tools into products: From MOOCs to microlearning over VR, Gamification and up next probably interactive learning. We really have a great variety of instruments at our hands for making education better.

But here’s my concern. Whenever a new technology enters the stage we can witness a repeating collective habit:

We get very excited about the new tool we’ve got and there are lots of articles on how it will “revolutionise education”

Then we rush to use it everywhere and bluntly apply it to just about any domain.

Let’s take one step back

What I am missing here is a critical reflection on why a given format would be the best way to teach the respective topic.

Say, how are gamified quizzes the best way to learn a language? Or why is microlearning the best way to teach job-related skills?

Which method we choose for a product appears to be very trend-driven. To me that speaks of a problem in how we approach the development process in general:

Currently, when we build EdTech solutions, the first thing we think about is the technology we want to use.

However, a technology or a learning format should never be an end in itself. It should be used intentionally as a tool to reach a clear learning outcome. Hence, I’d like to suggest a more scientific, first principles approach to product development in EdTech.

In this article, we will explore how we can refocus on learning outcomes and examine key principles of learning psychology. In the second part I will use a case study to show how we can integrate these insights into our education products.

Human Learning by First Principles

What makes a good educational offering, in my view, can be broken down to a simple formula:

It has to help learners to develop profound knowledge of a subject or proficiency in a skill. And it should do so effectively with regard to the time, money and effort they need to spend.

So, how do we achieve that?

Fortunately, we have quite a deep understanding of how humans acquire knowledge. And we also know how we can support that process. Both is mostly due to one domain of research: Learning Psychology.

Learning psychology as a dedicated discipline has been around now for almost 120 years. And the objective of scholars in the field has been exactly that: identifying the general mechanisms that lead to the formation of new knowledge, behaviour patterns and all sorts of skills.

Hence, their findings are great first principles to build on. When creating new EdTech solutions we can see them as a very extensive guidebook on how to design the entire learning experience.

Before we delve into using them in our products, I’ll provide a brief overview of what they are all about.

What are Psychological Models of Learning?

In short; every model is a general description of a process how humans do anything from memorising mere information, to understanding scientific concepts and developing practical abilities.

But as we typically understand things best from concrete cases, let’s skip the definitions. Instead we’ll look at two examples; each showcasing a different model.

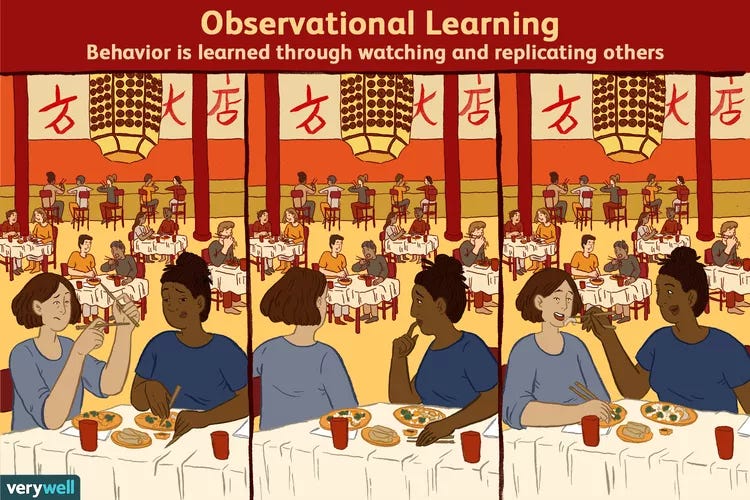

Skill-Acquisition through Observational Learning

Many of the skills we acquire during childhood and adult life can be traced back to a simple, yet potent mechanism:

We imitate the behaviour of people we observe.

Ever wondered how a child learns to speak so effortlessly? It may seem trivial, but it's all about observation and imitation. Children examine how their parents talk and over time identify patterns behind it. They start understanding which words and objects often go together and implicitly derive what they actually mean. Lastly, they try to imitate what they observed — at least to the degree they understand it.

But this goes much further than language learning: If you reflect on how you acquired certain abilities throughout your life yourself, you will find the mechanism of imitation over and over: Be it when you were picking up tricks from other kids on the football court, or when witnessing how a co-worker skillfully convinced a prospect to sign a contract:

We unconsciously generalise what we observed and apply our findings in situations, where we deem that behaviour to be helpful. We don’t reproduce by rote. Instead we make use of the underlying patterns of behaviour that we found during our observation.

This explains to a large degree how we learn “natively”, outside of formalised settings like schools. But we will see that we can also make use of this in organised learning experiences.

Credit: verywellmind

Grasping Abstract Concepts through Guided Discovery

Consider this: How did you first understand the concept of gravity? Or the intricacies of a mathematical equation? Was it through 'mechanical' learning, or did you 'discover' these concepts through examples and real-world applications?

When it comes to building up domain-specific knowledge, we develop a much more profound understanding when we make a finding ourselves. Guided discovery is all about leaving that moment of recognition to the learner.

Here we guide the learners towards understanding a topic by themselves, instead of preempting it. We don’t just tell them in general terms, e.g. “this is how photosynthesis works” or “this is what a math function does”.

Teaching gets very interactive: Step by step we provide examples, ask well-thought questions and give supportive information to make them grasp the entire logic behind a new concept themselves.

This benefits the learning process a lot. Any realisation that comes from one’s own reasoning is just much more profound and easier to transfer to practical problems.

Working with Learning Theories

There are some more things to note about these methods in general: none of them is really considered universal, in the sense that it’s relevant for every possible learning topic. We can see that in Observational Learning for example: It is a great approach to impart most types of skills, but not really compatible with teaching abstract knowledge, like e.g. the structure of an atom.

Consequently, we need to see for each topic, which methods actually make sense to apply. Fortunately, more than 120 years of research have given us a wide range of tools to choose from.

Understanding these principles is just the beginning. In the second part of this article, we will delve into we can apply them in our learning software, using a detailed case study on language learning.

We will explore how we derive a product concept directly from scientific findings. And we will find out how to choose a suitable technology based on logical reasoning, instead of trend.

You’ll see, we can learn a lot from these scientific models about how to design effective learning software. It really can enhance the outcomes for every single user.